*Originally published in Political Fiber, August 1, 2012

In a 1981 interview titled, “The Pleasure of Finding Things Out,” Professor Richard Feynman recounted the trauma he endured directly after the atom bomb (which he helped build) had been dropped on Hiroshima:

I felt very uncomfortable and thought, really believed, that it was silly – I would see people building a bridge and I would say, ‘they don’t understand.’ I really believed that it was senseless to make anything because it would all be destroyed very soon anyway – that they didn’t understand that. And I had this very strange view of any construction that I would see. I always thought, ‘how foolish they are to try to make something.’

Mere days had passed since the bomb had been used and a horrified Feynman was ready to do away with it.

On April 25, 2012, Professor Lawrence Krauss published a forceful appeal to American policymakers in Slate Magazine: “One of the simplest first steps toward escaping the nuclear menace that has haunted us for more than 65 years would be to encourage a worldwide ban on the testing of nuclear weapons.”

Although 157 states have ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, the United States has not. I’ll echo one of the most important points in Krauss’s article: The United States needs moral authority when it comes to nuclear weapons, and we won’t have it until a few drastic changes are made.

First, take Professor Krauss’s advice on the CTBT. To make his common-sense case even more straightforward, Krauss cites a recent National Academy of Science report on the technical objections to ratifying the treaty. The report found that the American nuclear stockpile could be safely maintained “whether or not the United States accepts the formal constraints of the CTBT.”

The obligations of the treaty itself are manifestly beneficial for both the environment and international cohesion. The United States will have an easier time rallying other countries against rogue, nuclear states such as North Korea if it relents on the CTBT. The arguments against ratification are crumbling while the case for doing so is getting progressively stronger.

Although the immediate effects of ratification would be immensely valuable, the entire nuclear age could pivot on the peripheral effects. Krauss couldn’t have penned his argument at a better time.

President Obama has repeatedly vowed to use “all elements of American power” to deny Iran a nuclear weapon. He’s on perfectly solid moral and logical ground. There is no conceivable reason to subject the Middle East to an unstable theocracy with devastating weaponry.

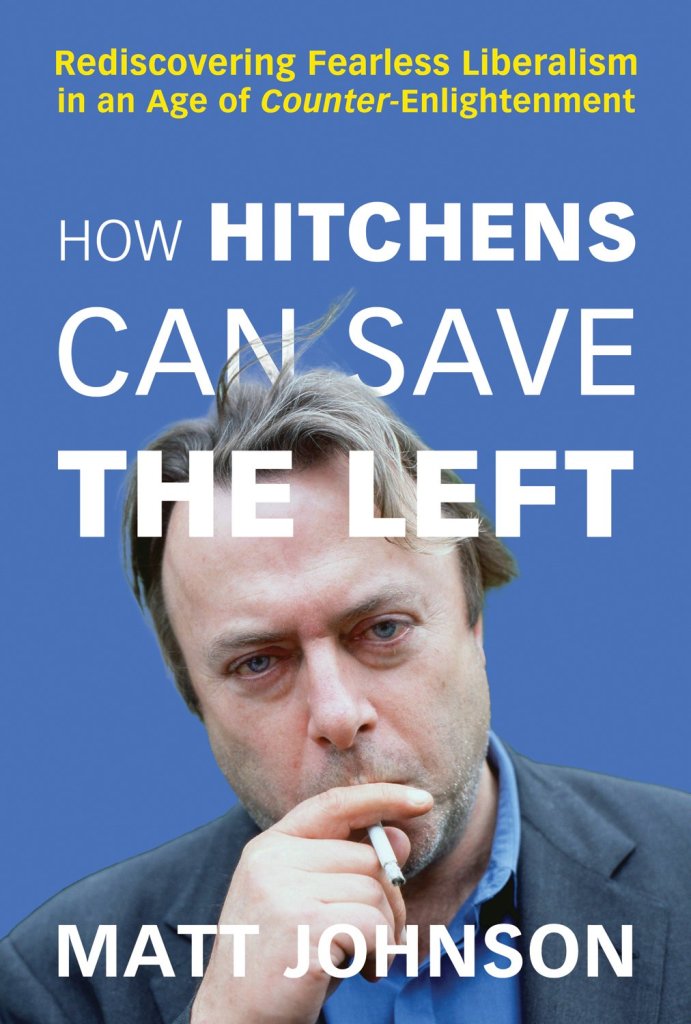

Still, Iran wouldn’t automatically launch a suicidal nuclear attack against Israel, nor would it arm a terrorist organization such as Hezbollah. But this doesn’t mean the bomb would be purely “defensive,” either. In a 2009 article for Slate titled, “Don’t Let the Mullahs Run Out the Clock,” Christopher Hitchens provides the most accurate analysis of the threat posed by a nuclear-armed Iran:

What they almost certainly will do, however, is use the possession of nuclear weapons for some sort of nuclear blackmail against the neighboring Gulf states, most of them Arab and Sunni rather than Persian and Shiite, but at least one of them (Bahrain) with a large Shiite population and a close geographical propinquity to Iran.

Hitchens helps to illustrate the inherent contradiction in Kenneth N. Waltz’s recent argument (which I addressed in my last article) and the obstinate belief that an Iranian bomb would be largely benign. Waltz believes that Iran desires a nuclear weapon for defense. Considering Iran’s aggressive behavior in the face of sanctions, its attempts to subvert Bahrain’s government, and its ignorance of the very real threats issued by the United States and Israel, defense seems an ancillary concern in Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons.

The United States has to prove that it’s serious about nonproliferation. This requires a two-pronged approach: decommissioning its nuclear arsenal and preventing other countries from acquiring nuclear weapons. With regard to the former, the Obama administration, in concert with the United States Senate and the Russian State Duma, recently took an encouraging step forward. The New START (Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty) entered into force on February 5, 2011.

New START marks only the beginning of a long road of nonproliferation shared by the world’s greatest nuclear powers, but it represents real progress. The fewer active nuclear weapons held by the United States, the more leverage it will have against countries like Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan (Israel too, for that matter).

The “peace sign” was originally the symbol for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the United Kingdom. It makes sense that it has grown from such a noble seed to a universally recognized emblem of international cooperation and prosperity. There are many different ways to stem the spread of nuclear weapons and reduce the risk of their deployment. Some, such as an American ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, are easy. Others, such as bombing Iran or choking it off with sanctions, are very difficult.

However, there are a few scholars (such as Kenneth Waltz) who would like to see more nuclear weapons aimed in every direction – aimed at all of us – the prisoners of what George Orwell called, “a peace that is no peace.” I, for one, would not.

Leave a comment